![]()

History of the R.M.S Titanic with historical photos and quotes from survivors

![]()

The late 1800 and early 1900's was a time of great change. With major advancements in technology life was becoming easier. Mark Twain called this time in history the "Gilded Age."

The Titanic's history begins in 1907 when the five year old International Mercantile Marine, formed when millionaire American J. P. Morgan purchased several shipping lines in 1902. With J. P. Morgan's money behind the White Star Line it was time to compete with the Cunard Lines Lusitania and Mauretania which had been causing the White Star Line to slowly lose profits. These ships were larger, faster and more elegant than anything the White Star Line had at the time. The White Star Line had to do something to win back the North Atlantic passenger traffic.

![]()

J. Bruce Ismay |

Thomas Andrews |

![]()

Lord Pirrie of the Harland and Wolff shipyards in Belfast, Ireland and J. Bruce Ismay, President of the White Star Line began discussing designs of three large steamers. The first ship is to be the Royal Mail Steamer (R.M.S.) Olympic and the second being the R.M.S. Titanic. The third was to be named Gigantic but was later changed to the R.M.S. Britannic. Harland and Wolff shipyards had to expand their building facilities to accommodate two large slips in which to build these new giant steamers. These ships were to be 882 feet in length, 92 feet across and 175 feet from keel to the top of the funnels. The man in charge of overseeing the construction of these ships was Thomas Andrews. During construction of these ships the shipyard employed up to 15,000 workers and craftsmen. During Titanic's construction several well known shipping publications told readers of the many safety features being built in to the new ships. The most noted of these were the 16 water tight compartments with water tight doors that could be closed from the bridge with the flip of a switch. The Shipbuilder magazine dubbed the Titanic "practically unsinkable". It was said that the Titanic could stay afloat with up to four of her water tight compartments flooded. It should be noted that the White Star Line never claimed the Titanic was unsinkable.

![]()

Water tight doors |

Workers at Harland & Wolff shipyards |

Titanic before launching |

Port, center propeller and rudder in dry dock |

Titanic's stern under construction |

![]()

R.M.S. Olympic was the first to sail, May 31, 1911, which was the same day the R.M.S. Titanic's hull was launched. Many people lined the areas around the Harland and Wolff shipyards to watch the large hull of the R.M.S. Titanic slide from it's slip into Belfast Harbor.

![]()

Launching of the Titanic |

Titanic during fitting out at Harland & Wolff |

Olympic docked beside Titanic in Belfast during fitting out |

![]()

By 12:15 the afternoon of May 31, 1911 the Titanic was afloat and being pulled to dry dock where it would spend the next year being fitted out. There were a number of changes made in the Titanic that differed from her sister ship the Olympic. After the Olympic's first sailing J. Bruce Ismay decided that the deck space was excessive and would be better used for additional staterooms. Two of which had their own fifty foot enclosed promenades.

![]()

Captain E.J. Smith on Titanic's aft A Deck or B Deck Promenade |

![]()

Some of the public areas were expanded as well and a French sidewalk cafe was added with real French waiters. The forward end of the first class A deck promenade was enclosed with sliding windows to better protect the passengers from the weather. These additions made the Titanic the largest ship afloat. Even larger, by tonnage, then her sister ship the Olympic.

![]()

Titanic leaving Belfast Harbor |

![]()

On April 3, 1912, after only eight hours of sea trials, the R.M.S. Titanic left Belfast, Ireland bound for Southampton, England and her maiden voyage scheduled for April 10, 1912.

![]()

|

|

|

|

Titanic leaving Southampton Pier at Noon on April 10, 1912 |

![]()

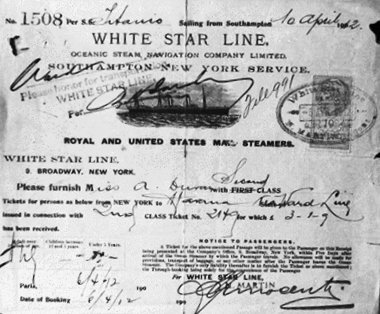

April 10, 1912 was departure day for Titanic's maiden voyage to New York via Cherbourg, France and Queenstown, Ireland. Captain of the R.M.S. Titanic was Edward J. Smith. He had been with the White Star Line for many years. He had been in command of over a dozen ships including the R.M.S. Olympic, Titanic's sister ship. He was well known and praised in the maritime community. Well liked by his crew and was very popular among frequent trans-Atlantic travelers. He had such a following that some passengers would not sail unless Captain Smith was commanding the vessel. He was known to some as the "Millionaire's Captain."

![]()

Captain E. J. Smith |

Notable Quotes from Captain Edward J. Smith "I can not imagine any condition which would cause a ship to founder. I can not conceive of any vital disaster happening to this vessel. Modern shipbuilding has gone beyond that." Adriatic, 1906 "When anyone asks me how I can best describe my experiences of nearly 40 years at sea, I merely say "uneventful." I have never been in an accident of any sort worth speaking about. I never saw a wreck and have never been wrecked, nor was I ever in any predicament that threatened to end in disaster of any sort." 1907 "Men, you have done your full duty, you can do no more. Abandon your cabin. You look out for yourselves, I release you. That's the way of it at this kind of time. Every man for himself." April 12, 1912, 2:10 a.m. speaking to Phillips and Bride |

![]()

Titanic departed Southampton at noon on Wednesday, April 10, 1912. On board were 337 First-class , 271 Second-class and 712 Third-class or steerage passengers. Among the First-class passengers on this maiden voyage were some of the worlds richest and most notorious people, such as John Jacob Astor, real-estate investor and his wife, Madeleine; Isidor Straus and his wife Ida, owners of New York's Macy's department store; Benjamin Guggenheim, millionaire playboy made his money from mining and smelting; George Widener, heir to the largest fortune in Philadelphia; Arthur Ryerson, steel company owner; William T. Stead, editor of the Review of Reviews; Sir Cosmo and Lady Duff Gordon, a dress designer; Major Archibald Butt, President Taft's White House aide; F.D. Millet, a well known artist of the time; Charles M. Hayes, president of the Grand Trunk Railway.

Shortly after departure she had a near collision with the American liner New York. Due to the Titanic's displacement and suction caused by her three propellers she pulled the New York from its moorings, snapping its ropes. The two ships were within about three feet of colliding. A collision was prevented by fast work on the part of Captain Smith by speeding up the port propeller to cause a wake to push the New York away and a tug that was close by.

![]()

New York being pulled away from the Titanic |

![]()

After this close mishap it was on to Cherbourg, France where it arrived at 7 p.m. She was anchored here for two hours while more passengers were tendered to her. At 9 p.m. Titanic departed for Queenstown, Ireland. She arrived at Queenstown the following day at 12:30 p.m. More passengers and mail were tendered to the Titanic. A great many of the Titanic's steerage passengers were tendered from Queenstown. At 2 p.m. Titanic left Queenstown for the open North Atlantic and New York. On board were 2,227 passengers and crew. By sundown the coast of Ireland was a distant memory. Everyone on board expected to arrive in New York six days later on Wednesday, April 17.

![]()

Titanic departing Queenstown for New York |

Aft Boat Deck on the Titanic |

Grand Staircase |

Cafe Parisien |

First Class Cabin |

First Class Smoking Room |

![]()

Passengers and crew were settling in to ship board routine. This was the grandest ship afloat and everyone was enjoying all of the extra luxuries. Everything was going smoothly a board ship until Sunday, April 14. Starting at 9 a.m. the Titanic's wireless room began getting ice warnings from multiple ships throughout the day. Not all of the ice warnings made it to the bridge or at least to Captain Smith's attention. There were several that did make it to the bridge, even J. Bruce Ismay was aware of several of the ice warnings. If all the ice warnings had gotten to the bridge and if they had been taken seriously they would have known there were heading into a large ice field.

There were church services held on board ship, First Class services with Captain Smith attending the services for the first class passengers held in the first class dining room on D deck. They were lead in a song that included the words, "For Those in Peril on the Sea."

By evening the passengers had noticed it was getting colder. After dinner most everybody was retiring to their warm cabins or in the public areas of the ship. By 9 p.m. the temperature was down to 33 degrees. At 9:30 p.m. Second Officer Lightoller told the carpenter to watch the fresh water tanks for freezing and told the lookouts in the crow's nest to watch for ice, "especially small ice and growlers", was the order from Lightoller. He also had a short conversation with Captain Smith and how cold it was and that the ship might be around the ice at any time. Nothing was said about slowing down. He advised Captain Smith what he had told the lookouts. Smith told Lightoller , "if it becomes at all doubtful" to call him.

![]()

First Officer Murdock |

Second Officer Lightoller |

Sixth Officer Moody |

![]()

At 10 p.m. the watch in the crows nest was turned over to Fredrick Fleet and Reginold Lee. The off going watch passed on the message to watch for small ice and growlers. At the same time First Officer Murdock took over the bridge from Second Officer Lightoller. The possibility of ice was mentioned at this time and Murdock was advised that the lookouts were watching for small ice and growlers.

At 11 p.m. the Lealand liner Californian attempted to warn the Titanic that she was stopped for the night on account of ice and was told to "Shut up, I am busy, I am working Cape Race." For Harold Bride and Jack Phillips it was their job to get passenger traffic delivered. Not to deliver messages for the bridge unless they were addressed directly to the captain. Any other messages would be delivered via messenger when convenient. Wireless as it was known was in its infancy. All of the communications were done by morse code. The operators did not work for the shipping lines but for the Marconi company. It was quite a novelty with passengers to be able to send messages to relatives, especially from the Titanic at sea. For this reason Phillips and Bride were back logged with messages. Their Marconi wireless had a range of 400 miles during the day and much farther at night. They were having good contact with Cape Race, Newfoundland and were trying to send as much passenger traffic as they could while conditions were favorable.

![]()

Fredrick Fleet |

11:40 p.m., April 14, 1912 |

First Officer Murdock |

![]()

At 11:39 p.m. Fredrick Fleet spots a large dark object in the distance. He rings the warning bell three times and called the bridge. The response from Sixth Officer Moody was "What did you see?", Fleet answers, "Iceberg Right Ahead", Moody responded with, "Thank you." First Officer Murdock was told of the iceberg and he ordered Quartermaster Hichens, "hard a starboard" on the wheel which turned the bow to port or left and he ordered the engines stopped and then full reverse. After what seemed like an eternity to the lookouts, the Titanic finally started to turn. It looked like they were going to clear the iceberg when at 11:40 a shudder vibrated through the ship. As they passed the iceberg it deposited ice on the forward well deck. Several passengers reported ice coming in their open portholes. Some passengers were awakened by the jolt and other were awakened by the commotion that followed.

![]()

Damage to the Titanic |

![]()

Thomas Andrews and the ship's carpenter were ordered to check the ship for damage. Sixth Officer Moody had gone below to look for damage and had not gone far enough and had reported back that everything was fine. Thomas Andrews however had gone to the boiler rooms and found that there was 14 feet of water in the forward compartments in the first 10 minutes. Andrews figured there was a gash on the starboard side below the water line at least 300 feet long. The forepeak, the two forward holds and boiler rooms 5 and 6 were open to the sea. He advised Captain Smith of this and gave the Titanic an "hour maybe two at most" to stay afloat. Shortly after midnight, Captain Smith gave the order for the boats to be swung out and loaded with women and children. Of the 2,227 people on board there was room in the 20 lifeboats for only 1,178.

![]()

Marconi Operators Jack Phillips and Harold Bride |

![]()

Just before 12:15 a.m. on April 15, Captain Smith came into the wireless room and told Phillips and Bride to send out the request for assistance because the ship was sinking. The Captain gave them their position by latitude and longitude. Phillips sent the following, "CQD MGY REQUIRE ASSISTANCE IMMEDIATELY, STRUCK BY ICEBERG 41.46 N 50.14 W. SINKING." MGY was Titanic's call sign. When Phillips was not getting any response with his initial calls with CQD, Bride suggested using SOS. It was the new morse code distress call.

With word spreading slowly and confusion among the passengers it was difficult to get them to the boat deck. The officers did not want to cause a panic. There were even stewards that were telling passengers they had thrown a propeller blade and to go back to bed or as Mrs. A. L. Ryerson was told when she called her steward to see what was going on, "there was talk of an iceberg ma'am, I suppose they have stopped as not to run over it." Some passengers did make it to the boat deck and found it too cold to stay outside waiting to get into the boats so they sought refuge in warmer places like the gymnasium. Here with many of the passengers riding the stationary bicycles or using the rowing machine, John Jacob Aster was cutting open a lifebelt to show his young pregnant wife what was inside. He later saw her off in boat number 4 when the officers in charge would not let him board. Also on the boat deck was the Titanic's band leader, Wallace Hartley and the seven musicians under him. Captain Smith had asked them to play to help comfort the crowd. This they did until the very end.

![]()

Gymnasium |

John Jacob Astor |

Titanic firing distress rockets |

![]()

By 12:45 a.m. the first lifeboat was lowered and Quartermaster Rowe had started firing distress rockets from the starboard bridge wing. They hoped to get the attention of a ship that many officers and passengers alike had seen off the port side about 5 or 10 miles away. Rowe even tried to reach her by using the morse lamp. The only ship that Jack Phillips had been able to confirm was coming to their aide was the Carpathia. She was 54 miles away and making 17 knots and would be to the Titanic's position in about 4 hours. Other ships including the Olympic could not comprehend that the Titanic was sinking and wondered if they were steaming south to meet her. Phillips had similar responses from other ships as well. This was more frustrating than anything for Phillips and Bride because they now knew the gravity of the situation. The ship had a very noticeable list toward the bow.

Officers were still having trouble getting passengers to believe that the Titanic was sinking. Why should they leave this large ship. As second class passenger Lawrence Beesley discribes it in his book about the disaster, "...to feel her so steady and still was like standing on a large rock in the middle of the ocean." Some of the boats were leaving with as little as 12 on board a boat meant to hold 40. A fireman coming up from below onto the forward well deck noticed the few people in the boats and asked, "If they are going to lower the boats, why don't they put some people in them?" J. Bruce Ismay gave Forth Officer Lowe some difficulty when he did not think he was lowering the boats fast enough. Lowe's response to Ismay was, "get out of the way of lowering the boats."

Shortly after 1 a.m. as lifeboat number 8 was being loaded, Mrs. Ida Straus, wife of Macy's Department Store owner Isidor Straus, was offered a place in the boat. She started to board and then changed her mind. She returned to her husband's side and said, "We have been living together for many years, and where you go, I go." She was urged to get into the boat by others and she responded with, "No, I will not be separated from my husband. As we have lived, so will we die together." Mr. Straus was then urged to get into the boat with his wife. He responded with, "I will not go before the other men." The Straus's quietly stepped back and blended into the crowd. They were later seen by Archibald Gracie as described in his story on the sinking, as sitting in steamer chairs on the enclosed A deck promenade. They were seen again later on the boat deck helping their maid into a boat.

![]()

Mr. and Mrs. Straus |

Titanic's bow under water about 1:30 a.m. |

![]()

At about 1:30 a.m. Titanic's bow and forward well deck were under water. Water was approaching B deck just below the bridge. Passengers were starting to panic now and First Officer Murdock stopped a rush on boat number 15. Benjamin Guggenheim was with his servant without their lifebelts and they had changed into their dinner clothes, he said, "We have dressed in our best and are prepared to go down like gentlemen." At about 1:40 a.m. as Collapsible C was being lowered after there was no more response to the call for more women and children, J. Bruce Ismay steps into the boat and saves himself.

![]()

J. Bruce Ismay steps into Collapsible C and saves himself. |

|

![]()

At about 1:55 Mrs. A. L. Ryerson observed the following as boat number 4 that she was in was being lowered, "The deck we left was only about twenty feet from the sea. All the portholes were open and the water washing in, the decks still lighted."

Shortly after 2 a.m. the stern was lifted far enough out of the water to expose the giant propellers. At 2:05 a.m. the last lifeboat to be lowered was Collapsible D. Collapsible B floats off of the boat deck overturned where it had landed in the attempt of crewmen to lower it from the roof of the officers quarters. As the over 1500 passengers still on board realize all of the lifeboats are gone they flock aft toward the steadily rising stern. There is also a large rush of steerage passengers from below. Steerage access to the boat deck was limited and there were reports of stewards keeping the steerage passengers below.

At 2:10 a.m. Phillips and Bride send their last call for help due to failing power. At this time Captain Smith walked in and told the two men, "Men, you have done your full duty, you can do no more. Abandon your cabin. You look out for yourselves, I release you. That's the way of it at this kind of time. Every man for himself."

This is when the band played their last song. Most of the survivors remember hearing the hymn Nearer My God to Thee and others remember haring the song, Songe d'Automne that was popular at the time. It has become the popular belief that the song heard was likely Nearer My God to Thee, it also may have been the later. None of the band members survived the sinking to tell the world for sure what was played.

There are several accounts of what happended to Captain Smith. In one account passengers and crew see him go to the bridge, another he is swimming with a baby which he passes into a lifeboat then swims away saying he is following the ship. In another he is said to have been seen shooting himself in the head. What really happened will never be known for sure, but he did go down with his ship.

Some time between 2:10 and 2:15 a.m. the first funnel snaps its ropes holding it in place and crashes into the sea killing many people that were in the water and washing the overturned Collapsible B away from the ship with several people who eventually used her for refuge the rest of the night including Second Officer Lightoller and Marconi Operator Harold Bride.

By 2:15 water was pouring through the dome roof over the Grand Staircase. The bow began to sink faster and faster with the stern rising farther out of the water. Most of the passengers still on board were now clinging to the rising stern. Father Byles was holding a prayer service with many people on the ever rising stern.

It was about this time when Thomas Andrews was seen standing at the fireplace in the First Class Smoking Room looking at a picture of Plymouth Harbor above the mantle in a daze. He ignored pleas from passengers and crew to save himself.

At 2:18 a.m. Titanic's lights flickered once came back on and then went out forever. The over 1,500 people left on board were now in complete darkness. As the stern rose higher and higher survivors remember hearing what they thought were the boilers breaking loose inside the ship. There were several survivors like Jack Thayer who said he saw the ship break in two. With the stern righting itself for a couple minutes then going vertical as it filled with water and sinking slowly away. Chief baker Charles Joughin was on the aft rail of the stern and said he just stepped off as the ship sank from under him. It was "like an elevator ride" as he described it. Not even getting his head wet and swimming away to later join the passengers and crew on overturned Collapsible B. In Collapsible C, J. Bruce Ismay looks away, not wanting to see the Titanic sink.

Mrs. Stephenson describes the sinking as follows from her perspective in lifeboat #4: " The lights on the ship burned till just before she went. when the call came that she was going I covered my face and heard someone call, 'She's broken." After what seemed a long time I turned only to see the stern almost perpendicular in the air so that the full outline of the blades of the propeller showed above the water. She then gave her final plunge and the air was filled with cries. We rowed back and pulled in five more men from the sea. Their suffering from the icy water was intense and two men who had been pulled into the stern afterwards died, but we kept their bodies with us until we reached the Carpathia, where they were taken aboard and Monday afternoon given a decent burial with three others.

At 2:20 a.m., April 15, 1912, 2 hours and 40 minutes after striking the iceberg, the greatest and largest ship in the world, Royal Mail Steamer Titanic, sank beneath the North Atlantic, taking with her more than 1,500 passengers and crew to their death. Hundreds of passengers were left to die of exposure in the 28 degree water. Along with several passengers and crew clinging to the overturned Collapsible B was Second Officer Lightoller, saying "She's gone."

Mrs. Thayer wrote the following about the sinking: "The after part of the ship then reared in the air, with the stern upwards, until it assumed an almost vertical position. It seemed to remain stationary in this position for many seconds, then suddenly dove straight down out of sight. It was 2:20 a.m. when the Titanic disappeared, according to a wrist watch worn by one of the passengers in my boat."

What followed for the next hour was what most of the survivors said they could not forget. The cries for help from the hundreds of people in the water. Crewmen were urged by passengers to go back and pull people from the water. Everyone was afraid they would swamp the boats. Quartermaster Hichens in boat number 6 told Molly Brown when she insisted on going back that "It is our lives now, not theirs." One boat did return to pick up survivors. Forth Officer Lowe organized several boats together and transferred his passengers to make room in his boat. He picked up 6 in all.

Survivors now floated in 20 lifeboats on the dark North Atlantic. Rockets were spotted at about 3:30 a.m. These were from the Carpathia as they approached the Titanic's last known position. As dawn approached the survivors could see many icebergs and field ice. This ice slowed the Carpathia's rescue efforts. By 8:30 a.m. all of the survivors were aboard the Carpathia. Just before 9 a.m. the Carpathia steamed for New York with 705 survivors on board. Titanic had started her trans-Atlantic trip with 2,227 passengers and crew, 1,522 perished.

![]()

Carpathia rescuing Titanic survivors |

Survivors in lifeboats as photographed from the Carpathia |

Titanic's sailing route and final resting place: April 10 at 12 Noon to April 15 at 2:20 AM, 1912. |

![]()

At 9 p.m., April 18, 1912 the Carpathia arrived in New York in a pouring rain. First the Carpathia went to the White Star Line pier to drop off the16 Titanic lifeboats it had salvaged. These lifeboats were all that was left of the world's greatest liner. Lawrence Beesley described the docking at New York, " ...the Carpathia drew slowly to her station at the Cunard pier, the gangways were pushed across, and we set foot at last on American soil, very thankful, grateful people." The world now learned the details of this great disaster.

![]()

Historical sources for this story:

Titanic: Death of a Dream Documentary, A&E

A Night to Remember, Walter Lord

The Night Lives On, Walter Lord

The Titanic: Death of a Dream, Wyn Wade

Titanic: An Illustrated History, Don Lynch and Ken Marschall

The story of the TITANIC as told by its survivors, Lawrence Beesley, Archibald Gracie, Commander Lightoller, Harold Bride

The Internet, Multiple Sites for Pictures and information

![]()

Click on the banner to return to the R.M.S. Titanic Page

![]()